Last updated on: December 27, 2025

Have you ever noticed that no matter how you try, you can’t fit a year perfectly into weeks? Your math teacher might have taught you that there are 12 months in a year, and if there are roughly 4 weeks per month, that should equal 48 weeks, right? But when you look at your calendar, you see 52 weeks instead. Maybe you’ve wondered why this doesn’t add up, or maybe you’ve never thought about it at all. Either way, you’re about to discover a fascinating mix of astronomy, ancient history, human superstition, and some surprisingly stubborn mathematics that explains why your calendar works the way it does.

This question keeps popping up in schools, online quizzes, and job interviews because it’s not just about basic division—it reveals something deeper about how we try to organize time itself. By the end of this article, you’ll understand the exact math, the wild history behind our calendar, and why our current system is actually the least broken solution humans have ever created.

How Long Is a Year—The Actual Number

Let’s start with the basic truth that most people get wrong: a year is not exactly 365 days.

The actual time it takes for Earth to complete one full orbit around the sun is approximately 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 45 seconds—or more precisely, 365.2422 days. That extra 5+ hours every year doesn’t sound like much, but it adds up quickly. Every four years, those leftover hours combine to create almost a full extra day, which is exactly why we have leap years.

For most of our daily lives, we round this to 365 days because dealing with fractions of days would be awkward. Your calendar says January has 31 days, February has 28 (or 29), and so on. But that rounding creates a problem: if the year were exactly 365 days with no extra hours, our seasons would slowly drift out of alignment with the calendar. Imagine celebrating the summer solstice on a winter day—that’s what would happen without leap years.

Leap years fix this problem. Every four years, we add an extra day (February 29th) to make the year 366 days instead of 365. This brings us closer to the true astronomical year. However, even leap years aren’t the final answer. The Gregorian calendar, which is what most of the world uses today, applies a more complex rule: leap years occur every 4 years, except for years divisible by 100, unless they’re also divisible by 400. This means the year 2000 was a leap year, but 1900 wasn’t, even though both are divisible by 4. This fine-tuning brings the calendar’s average year to exactly 365.2425 days, which is incredibly close to reality.

What Is a Week and Where Did It Come From?

A week has 7 days—Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday. This seems so natural to us that we rarely ask why 7. Why not 5 like a work week, or 10 like a nice round number? The answer takes us back thousands of years.

The 7-day week originated in ancient Babylon, around 4,000 years ago. The Babylonians were excellent astronomers, and they observed seven celestial bodies visible to the naked eye: the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. For them, the number 7 held special religious and magical significance, so they organized their calendar into 7-day cycles. Each day was named after one of these celestial bodies—which is why we still have names like Saturday (Saturn’s day) and Sunday (the Sun’s day).

Other ancient civilizations didn’t have 7-day weeks. The ancient Egyptians used a 10-day week, and the early Romans had an 8-day week called the nundinum. So the 7-day week wasn’t inevitable—it was just one choice that happened to spread widely.

Here’s where it gets interesting: the 7-day week spread globally not because it was mathematically perfect, but because powerful empires made it stick. When Alexander the Great conquered territories from Greece to India around 330 BCE, his Greek culture spread with him, including the 7-day week concept. When the Roman Empire expanded and conquered these same territories centuries later, they also adopted the 7-day week. In 321 CE, Roman Emperor Constantine officially decreed the 7-day week as the standard calendar unit for the entire empire and made Sunday a public holiday. After that, Christianity spread the 7-day week globally, and eventually it became the international standard we use today.

So the real answer to “why 7 days?” is part astronomy, part ancient belief systems, and part historical accident.

The Simple Math Behind 52 Weeks

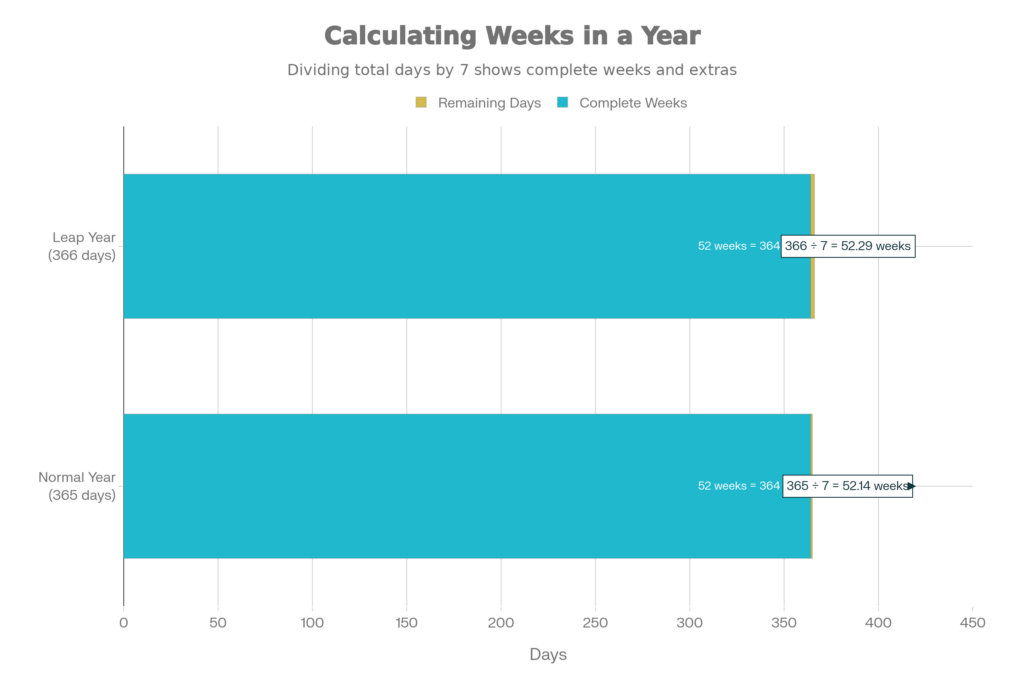

When you divide 365 days by 7 days per week, you don’t get a clean 52. Instead, you get 52 weeks with 0.142857 of a week left over. What does 0.142857 weeks mean? When you convert it back to days, it’s exactly 1 day. So a normal year contains exactly 52 complete weeks plus 1 extra day.

For a leap year with 366 days, the calculation is similar: 366 ÷ 7 = 52.285714, which equals 52 complete weeks plus 2 extra days.

Here’s why this matters: those leftover days don’t just disappear. They’re real days that have to fit somewhere in your calendar. You can’t ignore them or pretend they don’t exist. This is the core reason why a year can’t be 48 weeks—because 48 weeks would only account for 336 days, leaving 29 days unaccounted for every year. After a few years, your “calendar year” would be off by several months from the actual seasons, and soon your winter holidays would fall in the middle of summer.

Why Not 48 Weeks? Let’s Do the Math

If someone designed a 48-week calendar system, what would happen?

48 weeks × 7 days = 336 days

That’s 29 days short of the actual year. To make it work, you’d have to do one of two uncomfortable things:

Option 1: Make your days longer. If you stretched the day to 7.6 hours instead of 24 hours, 48 weeks would give you 364.8 days, almost enough. But then a “day” would be about 26 hours long, which breaks everything—your body’s sleep-wake cycle, your clocks, your entire concept of day and night.

Option 2: Make your weeks longer. If you created 8-day weeks instead, then 48 weeks would give you 384 days, which is too many. Your weeks would need to be adjusted, and you’d have to change how many weeks fit in a year anyway.

Option 3: Change the season/month structure. Some calendar reformers proposed having 13 months with exactly 28 days each. That gives you 364 days (13 × 28 = 364), so you’d add 1 “Year Day” as a floating holiday. Theoretically, this could work for timekeeping. But it would break the relationship between your calendar and the actual astronomical seasons, meaning spring wouldn’t start when it’s astronomically supposed to start.

The reality is that the number 365.2422 is not a friendly number. Its factors are 5 and 73, which don’t divide nicely. Because of this mathematical stubbornness of nature, there’s simply no way to create a perfectly regular calendar that also matches the seasons. The 52-week system is actually the least broken solution we’ve found.

Months vs Weeks—Why They Don’t Line Up Perfectly

You might have noticed that months aren’t actually 4 weeks long. February has 28 days (4 weeks exactly, almost), but March has 31 days (4 weeks plus 3 days), and so does May, July, August, October, and December. April, June, September, and November have 30 days (4 weeks plus 2 days).

Why does this weird pattern exist?

The confusion started with the moon. In many ancient languages, the word for “month” comes from the word for “moon,” because people originally tracked time by lunar cycles. The moon takes about 29.5 days to go through all its phases, from new moon to full moon and back to new moon. Twelve lunar months would give you 12 × 29.5 = 354 days, which is 11 days short of the actual solar year.

Ancient Romans, particularly King Numa Pompilius around 700 BCE, tried to create a calendar that matched both the lunar cycles and the solar year. He added extra months to the calendar to close the gap, but he ran into a cultural problem: Romans considered even numbers unlucky and odd numbers lucky (a superstition they shared with many cultures). So he made most months have either 29 or 31 days—odd numbers. The months alternated: 29, 31, 29, 31, etc..

But to reach the correct number of days for the year, one month had to have an even number. February was chosen to be this unlucky month with 28 days. Interestingly, February was already considered a month of misfortune because Romans performed funeral rites and purification ceremonies in February. So it made sense to them to give it the “bad luck” even number.

When Julius Caesar reformed the calendar in 45 BCE, he added 10 days to the total and shuffled things around. Pope Gregory XIII later fine-tuned this in 1582. But the core problem remained: the lunar month doesn’t match the solar year evenly, so months and weeks will never line up perfectly.

The Role of Ancient Calendars

To understand why we have 52 weeks today, it helps to know where our calendar came from. The story involves power, religion, astronomy, and a lot of trial and error.

The earliest Roman calendar had only 10 months running from March through December. The rest of the year wasn’t even officially tracked—people just thought of it as winter downtime when not much happened. This calendar had only 304 days, which made no sense astronomically.

King Numa Pompilius realized this was broken and added January and February to align with lunar cycles, bringing it closer to 355 days. But he also had to account for the fact that a true solar year is longer than 355 days. The solution was messy: a 27-day extra month called Mercedonius would be inserted between February and March every few years. Imagine the chaos—some years would have 13 months!

Julius Caesar’s Reform (45 BCE): When Julius Caesar came to power, the calendar was completely out of sync with the seasons. Historians reported that harvest festivals were being celebrated before crops were even planted because the calendar had drifted so far. Caesar hired the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes to fix this mess. Together, they created the Julian calendar, which simplified everything: a clean 365 days plus 1 leap day every 4 years, arranged into 12 months. This was revolutionary in its simplicity and worked pretty well for over 1,500 years.

The problem: the Julian calendar calculated a year as exactly 365.25 days, but we now know it’s actually 365.2422 days. That tiny difference of 0.0078 days per year doesn’t sound like much, but over centuries it adds up. By the 1500s, the calendar had drifted 10 full days away from the actual seasons.

Pope Gregory XIII’s Reform (1582): This drift was causing a serious religious crisis. Easter is calculated based on the spring equinox, and by 1582, Easter was being celebrated on the wrong date. Pope Gregory XIII assembled a team of scholars to fix the calendar. The solution was to skip 10 days in October 1582 (October 4 was followed by October 15) and create a more precise leap year rule: leap years every 4 years, except for century years (1700, 1800, 1900) unless they’re divisible by 400 (2000 was a leap year, but 1900 wasn’t).

This made the Gregorian calendar’s average year 365.2425 days, which is incredibly accurate and is why we still use this calendar today.

Why We Sometimes See “53 Weeks” in a Year

If you work in business, payroll, or project planning, you might have heard about years that have 53 weeks instead of 52. This happens, and here’s why.

The standard calendar year has 52 weeks because 365 ÷ 7 = 52 remainder 1, or 366 ÷ 7 = 52 remainder 2. But there’s an international system called ISO 8601 week numbering, which is used especially in business and government, that counts weeks differently.

In the ISO system, week 1 is defined as the first week that contains a Thursday. This means some years will have a complete 53rd week that wraps into the next calendar year, or a partial week that wraps from the previous year. According to this system, 53-week years occur when January 1 is a Thursday, or when it’s a leap year that starts on a Wednesday.

Recent examples include 2009 and 2015, and the next one will be 2026. Out of every 400-year cycle, exactly 71 years have 53 ISO weeks. For businesses using this system, a 53-week year affects everything from fiscal planning to payroll cycles to quarterly reports, so it’s worth paying attention to.

Could We Ever Change to a 48-Week Year?

Humans have tried. Many times. And failed every single time.

Throughout history, revolutionaries, scientists, and business leaders have proposed calendar reforms. Here are the most notable attempts:

The French Revolutionary Calendar (1792-1805): After the French Revolution, the new government decided to remake society—including time itself. They created a 10-day week and a 10-month year, renumbering from the “Year 1” of the revolution. This would have been interesting for mathematics, but the 10-day week felt unnatural after thousands of years of 7-day weeks. Citizens disliked the system, and when Napoleon took power, he abandoned the reform and returned to the Gregorian calendar.

The Positivist Calendar (1849): A French philosopher named Auguste Comte proposed renaming months after great historical figures—Moses, Homer, Aristotle, and others. It didn’t catch on because nobody wanted to celebrate “Homer’s month” instead of December.

The International Fixed Calendar (1902): A railway accountant named Moses Cotsworth realized that the Gregorian calendar was making his bookkeeping job a nightmare. Different months had different lengths, holidays fell on different weekdays each year, and calculating quarterly earnings was a pain. He proposed a calendar with 13 months, each with exactly 28 days (7 weeks × 4), plus a floating “Year Day” as a global holiday.

Here’s the clever part: in Cotsworth’s calendar, every month would be identical. The 1st would always be Sunday, the 5th would always be Thursday, the 13th would always be Friday (Friday the 13th every month!). Easter, Christmas, and every other holiday would fall on the same weekday every year, simplifying everything.

George Eastman, the founder of Kodak, loved this idea and tried to implement it within his company. He used the 13-month system internally for business planning. But Eastman knew that one company couldn’t change the world’s calendar alone. He and Cotsworth presented their proposal to Congress and to the League of Nations (the predecessor of the UN). The League of Nations considered 185 different calendar reform proposals, and the 13-month calendar was one of the finalists.

But here’s why it failed: there’s no single authority that can mandate a global calendar change. The Catholic Church had power to push the Gregorian calendar in the 1580s, but by the 1900s, the world was too diverse and politically divided. Even if all 185 calendar proposals were reduced to one perfect solution, getting the entire world to adopt it would require unprecedented cooperation. The League eventually gave up, especially after World War II made calendar reform seem trivial.

Why Modern Calendar Reform is Impossible:

Changing the calendar would affect every single person on Earth. Your birthday would shift. Contracts and legal documents would need rewriting. Religious holidays calculated by tradition would be affected. Schools would need to adjust. Financial systems would have to be reconfigured. The disruption would be enormous compared to any benefit. And without a single global authority, there’s no way to force everyone to switch at the same time.

So even though the Gregorian calendar isn’t perfect, we’re stuck with it—and honestly, 52 weeks is so much better than the alternatives that we should probably stop trying to fix what isn’t completely broken.

Fun Facts Most People Don’t Know

Now that you understand the core logic, here are some wild calendar facts that most people never discover:

Your Birthday Falls on a Different Day of the Week Every Year Because a year is 365 days (52 weeks plus 1 day), January 1 shifts one day forward each year. Your birthday does too. If you were born on a Wednesday, next year your birthday will be Thursday, the following year Friday, and so on. After leap years, it jumps two days forward instead of one. This is why some people’s birthdays eventually circle through all seven days of the week.

The Same Calendar Repeats Every 28 Years Here’s a cool pattern: in most cases, your calendar repeats exactly every 28 years. This is because 28 years contains exactly 7 leap years (every 4 years), and the total number of “extra days” from the leap years and regular years adds up to a multiple of 7 (a complete number of weeks). This realigns the calendar perfectly. So if you want to know what day of the week December 25 will be in 28 years, you can just look at this year’s calendar. The only exception is when century years disrupt the leap year pattern (like skipping 1900 but including 2000).

Date Shifting: Even within a single calendar year, the day of the week for a particular date shifts if you compare December 1 of this year to January 1 of next year. Since we have leftover days that don’t fit into complete weeks, the calendar gradually shifts all the dates forward by one day of the week.

Common Myths About Weeks and Years

Let’s clear up some misconceptions you might have heard:

Myth 1: “A year has exactly 52 weeks.”

False. A year has 52 weeks plus 1 day (or 2 days in a leap year). If it were exactly 52 weeks, a year would have only 364 days, and you’d lose over a full week per year. Within a few years, summer would become winter.

Myth 2: “A month is exactly 4 weeks.”

False. A week is 7 days, so 4 weeks is 28 days. Most months have 30 or 31 days. Only February (in non-leap years) comes close to 4 weeks. On average, a month is about 4.35 weeks.

Myth 3: “Leap years fix all calendar drift problems.”

Partially true, but not completely. Leap years fix most of the drift by adding back those extra hours that accumulate. But the Gregorian calendar’s more complex leap year rule (skipping leap years in certain century years) is what gets us really close to perfect. Even that isn’t completely accurate—it will take about 3,200 years for the Gregorian calendar to drift even one day from the true solar year.

The One-Paragraph Explanation

If someone asks you this question and you need to answer quickly, here’s your go-to explanation:

A year has 52 weeks because a year contains approximately 365 days, and when you divide 365 by 7 (the number of days in a week), you get 52 weeks with 1 day remaining. A 48-week system would only account for 336 days, leaving 29 days unaccounted for every year, which would cause the calendar to drift out of alignment with the seasons. The 52-week structure is the closest natural fit to Earth’s actual 365.2422-day orbit around the sun.

Why This Question Still Matters Today

You might be wondering: why should I care about any of this? It’s just how the calendar works, right?

Actually, this question matters more than you’d think, in real, practical ways:

In Education: This appears regularly on math tests, logic puzzles, and competitive exams. Colleges and employers ask it in interviews to see if you can think through problems systematically.

In Business: Companies need to understand fiscal quarters, payroll weeks, and project timelines. A 53-week year, for example, throws off quarterly budget comparisons unless you account for it. Project managers use ISO week numbering precisely to avoid confusion.

In Global Systems: When you’re working with international clients, contracts, and teams across time zones and calendars, understanding how our calendar system works is essential. Some countries still use different calendar systems for certain purposes.

In Personal Life: Understanding why your birthday falls on a different day every year, or why leap years exist, or why months aren’t evenly divided, connects you to how mathematics and astronomy quietly shape your daily life. It shows that even our most basic systems have history and logic behind them.

So, Why 52 Weeks and Not 48?

The simplest answer: math and astronomy, not choice.

A year has 365.2422 days because that’s how long it takes Earth to orbit the sun. A week has 7 days because ancient Babylonians observed 7 celestial bodies and that number stuck around. When you divide 365 by 7, you get 52 complete weeks with 1 day left over. There’s no way around it—you can’t ignore those extra days, and you can’t create a system that’s perfectly neat without breaking something else.

Every calendar system is a compromise between three things: the solar year (365.2422 days), the lunar month (~29.5 days), and human convenience. These three things never align perfectly. You can’t have 13 neat months, 52 neat weeks, and 365 neat days all at the same time. Something has to give.

We chose 52 weeks and 12 months because that’s the least broken solution. The Gregorian calendar—the one on your wall right now—is the result of 2,000 years of humans trying to get this balance just right. It’s not perfect, but it’s close enough that we haven’t changed it since 1582, and in our interconnected world, changing it would cause more chaos than it would fix.

So the next time someone asks you why a year has 52 weeks and not 48, you can tell them: because 365 isn’t 336, and nature doesn’t care about our preference for neat numbers.

FAQs

How many weeks are in a leap year?

A leap year has 366 days, which equals 52 weeks and 2 extra days. Mathematically: 366 ÷ 7 = 52.29 weeks.

What years have 53 weeks?

According to ISO 8601 week numbering, years with 53 weeks are those that start on Thursday or are leap years that start on Wednesday. Recent examples: 2009, 2026.

Why does February have 28 days instead of 30 or 31?

Roman superstition. King Numa Pompilius wanted all months to have odd numbers (considered lucky), but 12 odd numbers would sum to an even number. He chose February to be the “unlucky” month with 28 days. The Romans also associated February with death rituals, so they didn’t mind making it the shortest month.

Will we ever change to a different calendar?

Probably not. Throughout history, reforms have been proposed (like the 13-month calendar), but none gained global adoption. The coordination required and disruption caused would be too great.

Why is a year 365 days and not 360 or 370?

It’s not a choice—it’s determined by Earth’s orbit. Earth takes 365.2422 days to complete one orbit around the sun. That’s how long a year is, defined by physics and astronomy, not by human preference.