Last updated on: December 27, 2025

Think about your day. You wake up, check the time, and it reads 7 AM. You work for 8 hours. You eat lunch at noon. You go to bed at 11 PM. The numbers flow so naturally that you’ve probably never stopped to wonder: why 24? Why not 10 hours like the metric system? Why not 20? Why not some other number altogether?

Here’s the wild part: someone could have decided on a completely different system centuries ago, and you’d be living by those rules right now. Time isn’t a force of nature that works a certain way—it’s something we invented. And the story of how 24 hours became our global standard is far more interesting than you’d think.

Why 24 hours feels “natural”

To you, 24 hours feels like the obvious, only way to divide a day. But that’s because you’ve been born into this system. Your body has learned to expect it. Your routines fit into it. Everything in your world—your school schedule, your work hours, your favorite shows—is designed around 24. When something is everywhere, we stop seeing it as a choice and start seeing it as simply how things are.

Why it’s actually a human-made system

Here’s what you need to understand: the Earth rotates in approximately 23 hours and 56 minutes, not 24 hours. Nobody woke up one morning and said, “Let’s divide the rotation into 24 parts.” Instead, ancient civilizations looked at the sky, noticed patterns, used their fingers to count, and over thousands of years, settled on a system that worked. Then everyone else copied it. That’s it. That’s the entire reason.

What you’ll discover by the end

By the time you finish reading, you’ll know exactly why the ancient Egyptians picked 12 hours for day and 12 for night, why the Babylonians gave us 60 minutes per hour, why the French tried (and dramatically failed) to change the entire system during their revolution, and why your body would genuinely struggle if we suddenly switched to a 10-hour day. You’ll also understand why changing something this fundamental is practically impossible—even when someone comes up with a “better” system.

What Exactly Is a Day?

Earth’s rotation explained simply

A day is fundamentally about rotation. Your planet is a spinning ball, and as it spins, you experience daytime on the side facing the sun and nighttime on the side facing away. Simple, right?

But here’s where it gets interesting. The Earth’s rotation isn’t as straightforward as you might think. There are actually two ways to measure how long it takes for Earth to spin once:

One full spin = one day

When we talk about “a day,” we’re almost always talking about something called a solar day. This is the time between successive sunrises—the time it takes for the sun to return to the same position in the sky. A solar day is what appears on your clock: 24 hours.

But astronomers talk about something different: the sidereal day. This is how long it actually takes Earth to rotate 360 degrees relative to the distant stars. And here’s the shocker: that’s only 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds. Not 24 hours.

Why the difference? Imagine you’re on a merry-go-round while someone throws a ball at you from across the room. As you spin around, the ball’s position moves too. By the time you’ve completed one full spin, the ball has moved slightly closer to you. Earth does something similar: while it rotates, it’s also orbiting around the sun. By the time Earth has rotated once relative to the stars, it has moved slightly in its orbit. To face the sun again (which is what we actually care about for our daily lives), Earth needs to rotate about 4 extra minutes.

Why days are not exactly 24 hours long

The plot thickens. Even the 24-hour measurement isn’t perfectly accurate. Days vary slightly throughout the year because Earth’s orbit isn’t perfectly circular, and the planet’s rotation is affected by factors like atmospheric winds and ocean currents.

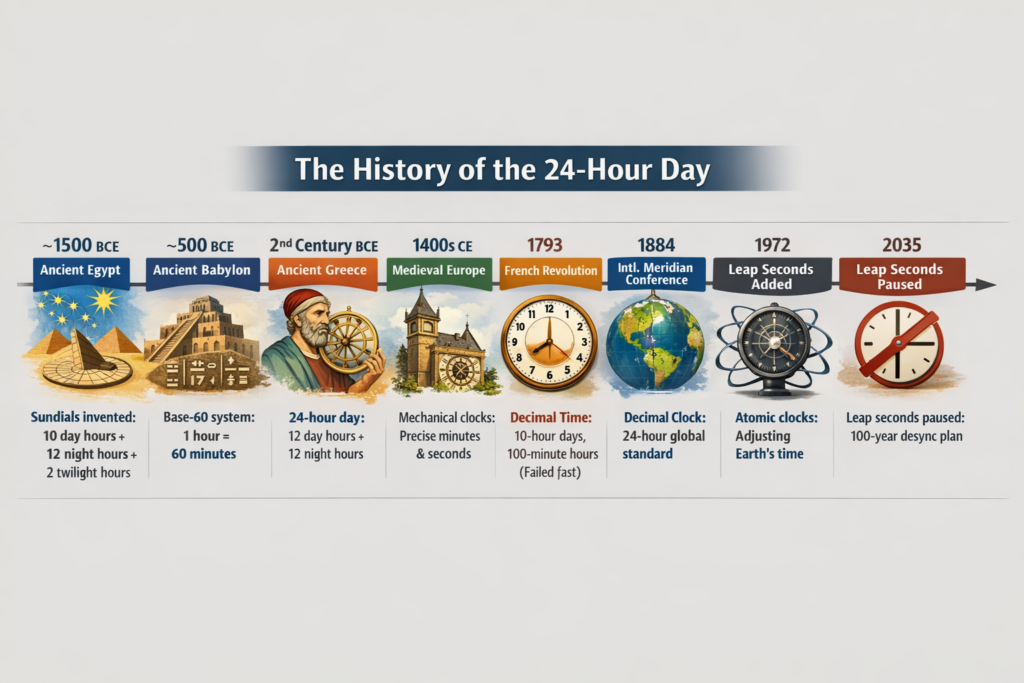

Scientists discovered this problem in the 1970s when they invented atomic clocks so precise that they could measure time accurate to a billionth of a second. These clocks revealed that the day isn’t exactly 86,400 seconds (which is what 24 hours equals). The difference is tiny—milliseconds—but over years and centuries, it adds up. Our clocks would slowly drift out of sync with the sun’s actual position.

This led to the invention of “leap seconds.” Roughly every 18 months or so, scientists add one extra second to global time to keep atomic clocks aligned with Earth’s actual rotation. You might not notice, but your computer’s clock technically experiences a moment that lasts 61 seconds instead of 60. It’s a bit like how we add leap years to keep our calendar aligned with Earth’s orbit around the sun.

Who Decided There Should Be 24 Hours?

Ancient Egyptians and sundials

The ancient Egyptians were the timekeepers of the ancient world. By around 1500 BCE, they had invented the sundial—one of humanity’s first clocks. It was elegantly simple: a stick (called a gnomon) casting a shadow on a surface divided into sections. As the sun moved across the sky, the shadow would move from section to section, showing how much of the day had passed.

Using these sundials, the Egyptians divided daytime into parts. But here’s the thing: they didn’t start with 12 hours. They started with 10. The logic was practical: they needed a number they could work with easily, and 10 was their comfortable count.

Why night and day were split first

Nighttime presented a problem. You can’t use a sundial when there’s no sun. So the Egyptians needed a different system for night. They looked up at the stars and noticed something remarkable: a specific group of 36 stars appeared in the night sky at regular intervals. Astronomers call these stars “decans,” and the Egyptians used them as celestial timekeepers. Every night, they could see 12 of these decans pass through the sky at predictable intervals.

This observation gave them an idea: if 12 decans marked 12 hours of night, and they had 10 hours of daylight, why not round it out? They added one hour at sunrise and one at sunset—the twilight periods when shadows were hard to see and stars were starting to appear. This gave them 12 hours of daylight (matching the night) and created a balanced, symmetrical system.

The role of shadow tracking

Shadows became the tool that made all this possible. The T-shaped shadow clocks the Egyptians used weren’t just practical; they were revolutionary. By carefully observing and measuring shadows throughout the day, ancient peoples learned to slice time into predictable, measurable chunks. This wasn’t something they invented overnight—it was refined over centuries as cultures watched, experimented, and documented.

The beauty of shadow tracking is that it’s observable and shareable. You don’t need complex instruments. You don’t need to be a genius mathematician. Anyone could look at a shadow and say, “Oh, it’s moved from section 3 to section 4. An hour has passed.” This accessibility meant the system could spread and become standard across an entire civilization.

Why the Number 24 Was Chosen

Base-12 and base-60 counting systems

Here’s a quirky fact: ancient peoples didn’t count the way you do. You probably count in tens—that’s why we call it the base-10 system. It’s natural for us because we have 10 fingers. But ancient Babylonians and Egyptians loved the number 12.

Why 12? Try this: use one hand to count. Your fingers have joints. If you use your thumb as a pointer and count the joints on your other four fingers, you get 12. Ancient people, who didn’t have calculators or computers, developed a finger-counting system that could reach 60 by using both hands in a clever way: one hand tracking sets of 12 (using those finger joints) and the other hand tracking how many sets of 12. That’s how the base-60 (sexagesimal) system was born.

This might seem random, but base-60 was incredibly useful for dividing things. It’s something mathematicians call a “highly composite number,” which means it has tons of factors. You can divide 60 by 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30, and 60. That’s 12 different divisors. For ancient peoples trying to split the day into equal parts, this was gold.

Why 24 is highly divisible

The Egyptians chose 24 for the day for essentially the same reason. Look at what 24 can be divided by:

-

2 (gives you 12 hours each)

-

3 (gives you 8 hours each)

-

4 (gives you 6 hours each)

-

6 (gives you 4 hours each)

-

8 (gives you 3 hours each)

-

12 (gives you 2 hours each)

That’s eight different clean divisions. For a society that needed to divide the day into workable chunks for tasks, prayer, and labor, this was perfect. You could split the day in half (2 halves of 12 hours). You could split it into quarters (4 quarters of 6 hours). You could create thirds, sixths, eighths. The flexibility was extraordinary.

Compare this to, say, 10. You can divide 10 by: 1, 2, 5, and 10. Only four options. If you needed to split a 10-hour period into thirds, you’d get 3.33 hours—awkward. You’d always end up with fractions, and before calculators existed, fractions were a headache.

Why this mattered before calculators

In a world without computers or even basic calculators, this divisibility wasn’t just convenient—it was essential. Merchants needed to split work into tasks. Religious communities needed to schedule prayers. Farmers needed to organize labor. The more easily a number could be divided into whole, clean pieces, the better it worked for everyone.

If you’re a mason building a wall and you have 8 hours of good daylight, and you need to split your workers into two teams with different tasks, 8 divides perfectly into 2, 3, and 4. You can have one team work 4 hours and another work 4 hours. Or you can split into three tasks of roughly 2-3 hours each. With a 10-hour period, you’d constantly be struggling with fractional hours.

This practical benefit is a huge reason 24 stuck around. It worked. Civilizations that adopted this system found it actually made their lives easier, so they kept it and spread it to others.

Why Not 10 Hours Like the Metric System?

The French Revolutionary time experiment

Picture this: It’s 1793. France is in the midst of revolution. The old system of measurement is chaos—different regions use different measurements for length, weight, and time. The revolutionaries decide to destroy the old world and rebuild it from pure logic. They invent the metric system: a base-10 system that makes everything divisible by 10. Meters, liters, grams—all base-10.

“Why stop there?” the mathematicians ask. “Why not fix time too?”

So they invent something called Decimal Time: a day divided into 10 hours, each hour into 100 minutes, each minute into 100 seconds. On paper, it was elegant. Want to know when the day is 70% complete? Simply: 7 hours, exactly. In traditional time, that’s 16 hours and 48 minutes. Decimal Time was mathematically beautiful.

On November 24, 1793, France officially switched. They printed new clocks with both decimal and traditional time. They educated people. They tried.

Why it failed badly

It crashed within 17 months.

Why? The reasons were surprisingly human:

People hated it. Every single person in France had been living by 24-hour days their entire lives. Their bodies expected certain patterns. They had internal clocks set to sunrise and sunset. A decimal hour was about 2.4 times longer than a traditional hour. Imagine if someone suddenly said your workday was now longer, your mealtimes shifted, and everything you’d ever learned about time was wrong. You’d resist too.

It was expensive. Every clock in the country needed replacing or modification. Every watch needed adjustment. The government was already spending money on the revolution, the military, and reform. Asking people to replace all their timekeeping devices wasn’t realistic.

There was no practical benefit outside of math. Here’s the critical difference between Decimal Time and the metric system: the metric system revolutionized commerce. Suddenly, a merchant in Paris and a merchant in Lyon could trade using the same measurements. Previously, weights and measures had been wildly different across regions. The metric system solved a real problem.

But clocks? Time was already standardized globally. Everyone already knew the 24-hour system. Switching to Decimal Time didn’t help anyone trade better or communicate more clearly. It just made everything confusing.

Why humans rejected decimal time

The French government issued an official order on April 7, 1795: Decimal Time was no longer mandatory. After just 17 months, they gave up.

Some parts of France continued using it for years afterward, which led to exactly what you’d expect—missed meetings, confusion, and frustration. Imagine showing up for an appointment and one person is thinking in decimal time while the other is thinking in traditional time.

The failure of Decimal Time teaches us something crucial about how change actually works. It’s not about which system is mathematically superior. It’s about what people are accustomed to, what actually solves real problems, and how much disruption society is willing to tolerate. A “better” system means nothing if people won’t use it.

France tried again in 1897, proposing a compromise: keep the 24-hour day but use 100 decimal minutes per hour. Even that was rejected by 1900. The world had decided: 24 hours was staying.

How Minutes and Seconds Came Into the Picture

Babylonian influence (base-60)

After the Egyptians gave us 24 hours, time needed further subdivision. The ancient Babylonians, who absolutely loved base-60 math, had the answer.

The Babylonians were master astronomers. They studied the stars with remarkable precision and developed the base-60 system for detailed calculations. When Greek astronomers (who came later) needed to divide hours into smaller units, they adopted the Babylonian approach.

Why 1 hour = 60 minutes and 1 minute = 60 seconds

This wasn’t random. Just like 24 is highly divisible, so is 60—arguably even more so. Sixty can be divided by: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30, and 60. That’s 12 divisors.

Mathematicians of the time understood that 60 was the smallest number that could be divided evenly by 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. For astronomers trying to measure the precise positions of stars and predict planetary movements, 60-based division was ideal. It meant they could measure angles and time with fewer fractions.

Why this system still survives today

Here’s the interesting part: we’re not using Babylonian base-60 anymore for everyday math. We’ve switched to base-10. We use metric measurements. We do calculations on computers that work in binary. Yet we still say “60 minutes in an hour” and “60 seconds in a minute.”

Why? The same reason 24 hours survived: inertia and practical benefit. Once the system was established and people learned it, changing it caused more problems than it solved. Plus, time measurement is actually one area where base-60 still offers advantages. Astronomers and navigators still appreciate the mathematical convenience.

So we’re left with a beautiful historical artifact: our time system is a mix of Egyptian 24-hour division, Babylonian 60-minute/second division, all wrapped up in a 10-digit number system we use for everything else. It’s contradictory and weird, but it works.

The Real Length of a Day (It’s Not Exactly 24 Hours)

Sidereal day vs solar day

Remember earlier when we talked about the difference between a sidereal day and a solar day? Let’s go deeper.

A sidereal day is 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds. That’s the time it takes for Earth to make one complete 360-degree rotation relative to distant stars. From an astronomer’s perspective, this is the “true” rotation of the planet.

But your life doesn’t operate on a sidereal day. Your life operates on a solar day—24 hours—which is measured by the sun’s position in the sky. The sun appears to move around Earth once per solar day.

The difference exists because of Earth’s orbit. While Earth rotates, it’s also moving around the sun. After a complete rotation (23 hours 56 minutes), Earth has moved slightly in its orbit. To complete a full rotation and face the sun again, Earth needs about 4 extra minutes. That’s why a solar day is about 24 hours, and that 4-minute difference means there are about 366 sidereal days in a year but only 365 solar days.

If you’re wondering whether this affects your life: not really. Your calendar and clocks operate on solar days, which is what matters for when the sun rises and sets, when you eat and sleep, and when you work.

Leap seconds explained simply

Here’s where it gets truly wild. In the 1970s, atomic clocks became so accurate that scientists realized something alarming: the length of a day varies. Sometimes it’s slightly longer, sometimes slightly shorter. Additionally, Earth’s rotation is gradually slowing down over very long timescales (by fractions of a second per century).

The problem: atomic clocks (which measure time as a fixed number of oscillations) and Earth’s rotation (which varies) were drifting apart. If nothing was done, eventually the sun would be rising at midnight on your calendar.

The solution: leap seconds. Every 18 months or so, timekeepers around the world add an extra second to the official time. Instead of going from 23:59:59 to 00:00:00, you get 23:59:59, then 23:59:60, then 00:00:00. It’s a moment that lasts 61 seconds instead of 60.

Why clocks need adjustment

This adjustment exists to keep our atomic time synchronized with the Earth’s actual rotation. It’s a compromise between perfect mathematical time (which doesn’t exist in nature) and the actual planet we live on (which refuses to cooperate with our schedules).

The catch? Leap seconds cause havoc for computer systems. When billions of connected computers suddenly have to process a 61-second minute simultaneously, bugs and crashes can occur. For this reason, in 2022, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures voted to eliminate leap seconds starting in 2035. They’ll allow the difference between atomic time and Earth time to grow to about a minute before doing anything about it. That’s acceptable because over the next century or so, the cumulative error will be manageable.

What Would Happen If We Changed to a 10-Hour Day?

Impact on sleep cycles

Your body isn’t a clock. It’s a biological machine that has evolved over millions of years to synchronize with Earth’s 24-hour rotation.

Inside your brain is a region called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (or SCN for short). This tiny structure is your body’s master clock. It responds to light and darkness, regulating your sleep-wake cycle (called your circadian rhythm). Your SCN doesn’t just affect when you’re sleepy; it controls your body temperature, hormone production, appetite, metabolism, and countless other processes—all timed to a roughly 24-hour cycle.

Here’s what’s fascinating: your natural circadian rhythm is actually close to, but not exactly, 24 hours. Research shows humans can adjust to cycles as short as 23.5 hours or as long as 24.65 hours. So technically, a 10-hour day isn’t impossible.

But it would be miserable.

If you suddenly switched to a 10-hour day, your sleep cycle would be completely out of sync with your wake-sleep schedule. You’d probably feel jet-lagged constantly—which is what happens when your circadian rhythm doesn’t match your actual schedule. Your body would produce melatonin (the sleep hormone) at the wrong times. Your cortisol (the wake-up hormone) would surge at weird hours.

You’d be fighting your own biology. Imagine working 4 hours, sleeping 3 hours, and trying to fit everything else in 3 hours. Your body would rebel.

Impact on work, school, and business

Beyond your biology, society would collapse. Well, not completely—but everything would need to be redesigned.

An 8-hour workday would become a 3.2-hour workday. Wait, does that sound better? No, because a 10-hour day is only about 2.4 times longer than a traditional hour. So while you’d have shorter “workdays,” you’d have shorter “sleep nights” too. Your work wouldn’t feel easier—it would feel more fragmented.

Schools would need to restructure completely. A typical school day is 6-7 hours long. In a 10-hour day system, that would be about 2.5-3 hours. You couldn’t fit all the classes. Everything would be condensed and rushed.

Business would be chaotic. International commerce already struggles with time zones. Imagine if the problem was even worse—if “an hour” meant something different from what it used to. Financial markets operate on precise timing. A mistake in scheduling could cost millions. Supply chains rely on synchronization. Switching to 10-hour days wouldn’t just be inconvenient; it would be economically destructive.

Why your body clock would struggle

The fundamental issue is this: humans spent millennia evolving bodies that work on a 24-hour cycle. Your cells, hormones, digestion, and metabolism are all tuned to this rhythm. Even if you consciously wanted to adapt to a 10-hour day, your body’s internal processes wouldn’t cooperate.

Studies on shift workers—people who work irregular schedules that fight against their circadian rhythm—show consistent problems: weight gain, metabolic dysfunction, increased risk of diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. Imagine forcing everyone on Earth to be a shift worker. The public health consequences would be severe.

Why Time Feels Faster as You Grow Older

Brain perception of time

This isn’t just a feeling—there’s actual neuroscience behind why your childhood summers felt infinite and why years blur together as an adult.

One theory comes from physicist Adrian Bejan. He argues that our brains process information at a certain rate. As we age, the neural networks in our brains become larger and more complex. Electrical signals have to travel farther between neurons. This means the brain processes information slower—fewer “frames per second,” so to speak. Time, which is based on how many distinct moments we perceive, feels like it’s speeding up.

Think of it like a video. If you watch a video at 24 frames per second, it looks normal. But if you watch it at 12 frames per second, it looks sped up and choppy. Your aging brain is showing you fewer frames, so the day rushes by faster.

Why childhood days felt longer

When you’re eight years old, a week is a huge portion of your life. You’re 8 years old, so a week is 1/416th of your existence. When you’re 80 years old, a week is 1/4,160th of your existence—ten times smaller as a fraction. This is sometimes called the “log time” theory.

But that’s not the whole story. There’s also the novelty factor. When you’re a kid, everything is new. Your brain is encoding new experiences rapidly—learning the alphabet, learning to ride a bike, discovering what pizza tastes like. Your brain records these rich, detailed memories. Looking back, those days feel packed with experiences, so they feel longer.

When you’re an adult doing the same commute, the same job, the same routine, your brain doesn’t encode those days as richly. It’s not creating new memories. Without distinct, memorable moments to reference, weeks blur together.

Why adults feel time “flies”

The key to feeling like time moves slower is novelty. When you try something new—a different route to work, a new hobby, a new food—your brain creates new memories. Those memories add substance to your days, making them feel more substantial in retrospect.

This is actually actionable: research from University of Michigan psychology professor Cindy Lustig shows that people who deliberately introduce novelty into their lives—new experiences, new challenges, new learning—perceive time as moving more slowly. Adults who keep doing the same things experience time flying by because their brains have nothing new to file away.

So if you feel like time is slipping away too fast, you can actually slow it down. Not by changing the clock, but by filling your life with experiences your brain finds worth remembering.

Common Myths About Hours and Time

“Time is a natural unit” (False)

Many people think time is something that exists in nature—like gravity or heat. But time measurement is completely invented. The sun rises and sets, yes, that’s natural. But dividing that cycle into 24 parts? That’s human choice.

Other planets have different day lengths. Venus takes 243 Earth days to rotate once. A day on Jupiter is about 10 hours. If you lived there, your natural day-length would be completely different. You might have evolved a circadian rhythm synchronized to a 10-hour day—and the Jovian equivalent of the French would never dream of changing it.

“24 hours is scientifically perfect” (False)

Some people think that scientists studied Earth’s rotation and decided 24 was the optimal, scientifically correct number. This isn’t true. The ancient Egyptians chose 24 based on finger-counting and mathematical convenience, long before any scientific instruments existed. It worked for them, and it happened to align reasonably well with Earth’s rotation, so it stuck.

If we’d discovered that Earth’s rotation was 23 hours or 25 hours, we probably would have adjusted our system. Instead, we just added leap seconds to paper over the difference. There’s nothing sacred about 24—it’s just what happened to become standard.

“We can easily change it” (False)

This is the most important myth to bust. The Decimal Time experiment proved it. No matter how logical a new system is, if it disrupts billions of people’s lives and costs enormous sums to implement, it won’t happen.

Changing time would require:

-

Reprogramming every computer and digital device on Earth

-

Rewriting software that controls critical infrastructure (power grids, transportation, financial systems)

-

Retraining entire populations

-

Restructuring every business, school, and organization

-

Dealing with months of chaos as old and new systems transition

The cost would be in the trillions of dollars. The disruption would be catastrophic. The benefit? Mathematically, maybe 10-hour days are slightly cleaner than 24-hour days. But that’s nowhere near enough reason to flip the switch.

This is why systems that are “good enough” tend to persist forever, even when better alternatives exist. Once billions of people are using something, switching becomes practically impossible.

A day has 24 hours because ancient civilizations divided daylight and darkness into equal parts using base-12 counting systems. The number 24 was easy to divide mathematically (divisible by 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 12), which made it incredibly practical before calculators existed. The ancient Egyptians developed this system using sundials and star observations, and it became the global standard long before modern clocks existed. When the metric system was invented, the French even tried to switch to 10-hour days in 1793, but the system failed because people were already accustomed to 24 hours and the cost of change was too high. Today, 24 hours persists because billions of people and systems depend on it, and changing it would cause more problems than it would solve.

Why This Question Still Matters Today

Used in competitive exams

If you’re preparing for any competitive exam—SAT, GRE, IAS, NEET, or similar—questions about time measurement, Earth’s rotation, and the history of timekeeping show up regularly. Understanding the why behind 24 hours gives you the context to answer related questions about solar days, sidereal days, and time zones.

These questions often appear in science sections, geography, and even in verbal reasoning (because understanding historical context improves comprehension). The story of Decimal Time, for instance, appears in history and science curricula worldwide.

Relevant to space science

Space scientists and astronomers use both solar and sidereal time constantly. If you’re studying astronomy, astrophysics, or planning missions to space, understanding why we have 24 hours and how it differs from astronomical time is essential.

Missions to other planets involve calculating how a day differs on that planet. Mars has a day (called a sol) of 24 hours and 37 minutes—close to Earth but slightly different. Understanding time systems helps you grasp how we schedule operations and communicate with rovers and probes.

Affects global synchronization

The 24-hour system is one of humanity’s greatest achievements in coordination. Every person on Earth—from a farmer in India to a trader in New York to a scientist in Antarctica—synchronizes their activities using the same 24-hour framework. This is why air traffic works without constant collisions. This is why international financial markets coordinate. This is why you can video call someone across the world and know you’re not waking them up at 3 AM (well, unless you miscalculate time zones, but that’s a different issue).

Understand the 24-hour system, and you understand one of the invisible systems holding modern civilization together.

Conclusion: Why 24 Hours Still Works Best

Historical inertia

The biggest reason 24 hours persists is simple: it’s what we’ve always had. Humans are creatures of habit. We learn systems and stick with them. After 3,500+ years of 24-hour days, our entire civilization is built around this rhythm.

Once a system becomes embedded in society—in our institutions, our laws, our technologies, our bodies—changing it requires more willpower and resources than accepting its quirks. This is called “path dependence,” and it explains why we use QWERTY keyboards (designed for mechanical typewriters), why electrical outlets differ by country (because each country chose their own standard before global coordination existed), and why our time system combines Egyptian hours with Babylonian minutes.

Mathematical convenience

The 24-hour system still works beautifully mathematically. Divisibility by 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 12 means that for most practical purposes, the day divides evenly. Before digital tools existed, this mattered enormously. Even today, there’s elegance to it.

And the base-60 system for minutes and seconds? Still brilliant for astronomy and precision measurement. We could do all calculations in base-10, but base-60 actually has advantages that mathematicians still appreciate.

Human biology compatibility

Most importantly, 24 hours aligns with how our bodies work. Our circadian rhythms evolved to match Earth’s 24-hour rotation. When our schedules align with this natural rhythm, we sleep better, our metabolism works more efficiently, and we’re generally healthier.

A 10-hour day would fight against billions of years of evolution. A 20-hour day would be awkward (less divisible than 24). A 12-hour day would mean fewer working hours. Every alternative creates problems.

The bottom line

The reason your day is 24 hours has nothing to do with what’s scientifically optimal or mathematically perfect. It’s the result of accident, evolution, cultural choice, and the sheer inertia of billions of people depending on the same system.

The ancient Egyptians could have chosen 12 hours or 20 hours. History could have gone a different way. But they chose 24, and it stuck. The French tried to change it and failed spectacularly. Everyone after them learned from that failure: once a timekeeping system is embedded in civilization, you can’t change it, no matter how logical your alternative is.

So tomorrow morning, when your alarm goes off, remember: you’re waking up to a system invented by ancient civilizations that simply never fell out of favor. Your 24-hour day is a 3,500-year-old artifact that somehow remains perfect for the modern world.

FAQs

Who invented the 24-hour day?

The ancient Egyptians developed the 24-hour day system around 1500 BCE. They divided daytime into 10 hours (and later 12), observed 12 stars (called decans) in the night sky, and added twilight hours to create a balanced 24-hour cycle. Later, the Greek astronomer Hipparchus standardized it as 12 equal hours of day and 12 equal hours of night.

Why didn’t we switch to 10-hour days like the metric system?

France attempted this during the Revolution in 1793, introducing “Decimal Time” with 10-hour days. It failed within 17 months because people were deeply accustomed to 24-hour days, replacing every clock was expensive, and unlike the metric system, it didn’t solve any practical problems. The system caused confusion and people resisted change.

Why are there 60 minutes in an hour instead of 100?

The 60-minute division comes from the ancient Babylonians, who used a base-60 counting system. The number 60 is highly divisible, making it mathematically convenient for detailed measurements. Greek astronomers adopted this system for astronomical calculations, and it became standard worldwide.

Is a day exactly 24 hours long?

Not exactly. A solar day (time between successive sunrises) averages 24 hours. But Earth’s sidereal day (one complete rotation relative to stars) is 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds. Additionally, Earth’s rotation varies slightly daily. Scientists use leap seconds to keep atomic clocks synchronized with Earth’s actual rotation.

Would our bodies adjust to a 10-hour day?

Unlikely without major health consequences. Human circadian rhythms have evolved over millions of years to synchronize with Earth’s 24-hour rotation. Research on shift workers—people with irregular schedules—shows increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. A 10-hour day would create perpetual biological jet lag for everyone on Earth.